TUESDAYS were days off for dental nurse Gillian Birch. She usually got up late and then looked forward to a lunchtime piano lesson. On the winter morning of January 29, 1985, still dressed in her nightclothes, she waved goodbye from a bedroom window as her 50-year-old husband and teenage daughter left in his yellow Fiat to feed the family pony stabled a 10-minute drive away. It was 7.15am.

Just over an hour later Michael Birch would return home carrying a black handled, serrated edged knife he used to cut string on hay bales and plunge it four and a half inches into his wife’s body, passing through a lung and into her heart. The failed businessman was taking one last monstrous gamble before bankruptcy ruined him.

He hoped his wife’s £70,000 life insurance would solve all his problems. In reality the evil, callous deed led him only to a life in prison.

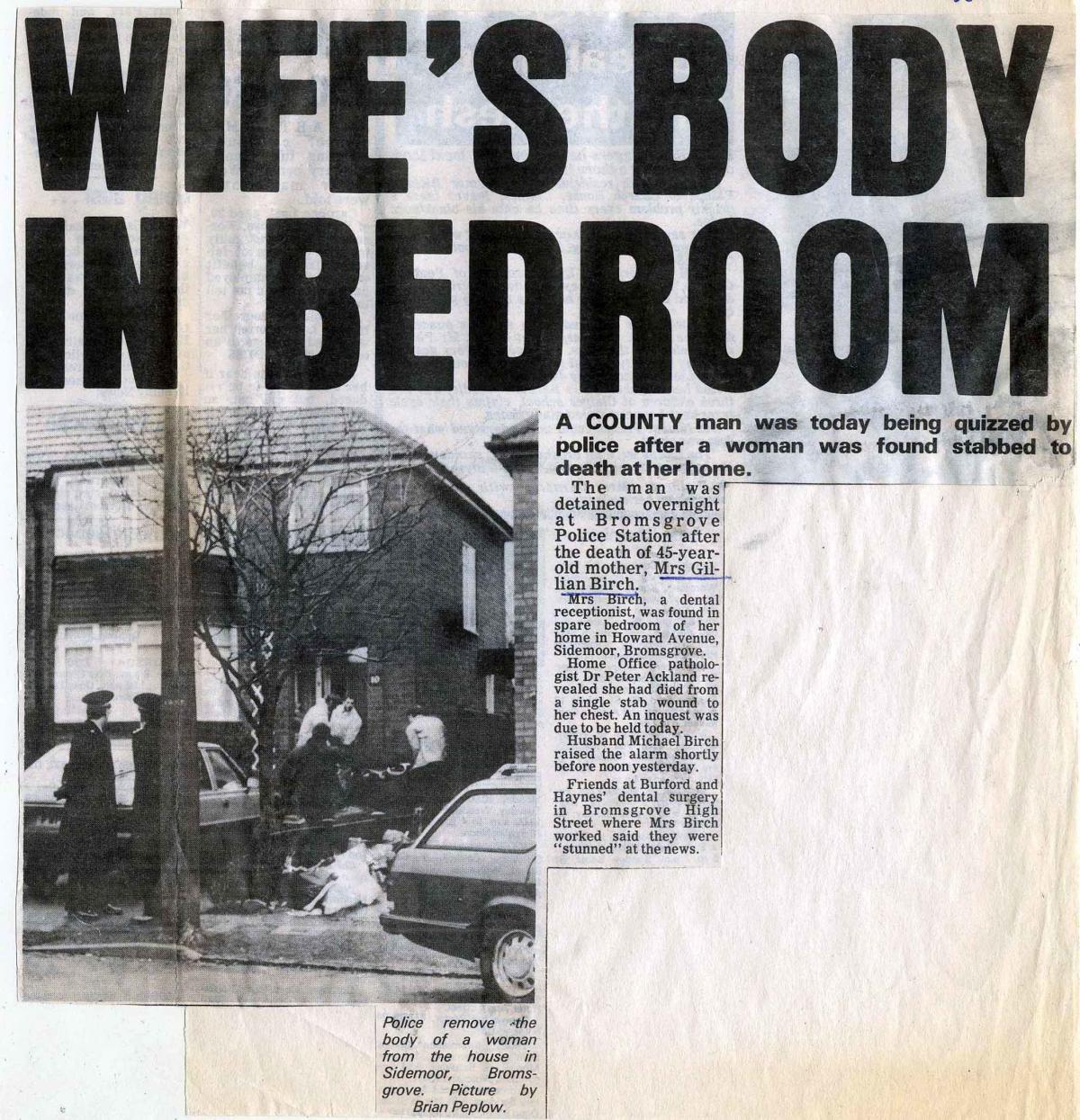

A jury at Hereford Crown Court heard that in a bedroom he used as a study in their home in Howard Avenue, Bromsgrove, Birch killed his caring wife without mercy and then tried to rid himself of incriminating evidence.

The couple had been keen members of a drama group in nearby Rubery, even appointed life vice presidents, but Birch’s amateur acting skills did not fool West Mercia detectives. As one of them was later to observe: “During interviews and even in the dock, Michael Birch often started crying, but we noticed there were never any tears.”

He was undone by the dogged police work of a team, led by Det Supt Barry Mayne, which eventually exposed the murder plot hidden under a tangled web of deceit.

Michael and Gillian Birch, who was 44 when she died, married in June, 1961, the union, according to Birch, being “a perfect mix”. He saw himself as the emotional romantic given to eccentricity and even black moods of depression. His wife he described as dependable, calm and loving. She became his first insurance customer and later handed over cash from her mother’s will to back his doomed business ventures.

Birch, maverick by nature, flitted between jobs. He was a bank clerk, council housing clerk, record shop owner, accountant, computer worker and factory hand. Despite being a high achiever at grammar school, he gained no formal professional qualifications and tagged himself a financial consultant, setting up in insurance in 1979.

For a while he worked closely with the Anglia Building Society, but when it severed their ties he lost a huge chunk of his income. As disenchantment with the financial world set in his mental state began to deteriorate. He embarked on two affairs, one ending when the woman died in a car crash. Meanwhile his wife’s health had begun to go downhill and the Bromsgrove dentist for whom she worked told police he believed it was because of pressure at home.

At this point Birch set up his final company called Creative Graphics, but money only trickled in. The pressure mounted and he began to yearn for a pastoral life. He came to believe he would have found happiness as a farm labourer in his beloved Wales, the land where he was born.. He wanted peace and quiet, but all around him his wayward life was closing in on him. He was double mortgaged, had HP debts, owed a garage £500 (around £1,500 today) for petrol, ran two cars, put his daughter through private school and took out a £3,000 bank loan on computer equipment.

He had cancelled insurance policies on his own life, but significantly kept his wife’s paid up. He knew he needed to find another £13,500 by May, 1985, money which had been given to him to invest, but which had found its way into his own company to prop it up.

Exactly when Michael Birch hatched the plot to kill his wife was unclear to detectives, but they knew he had been pestering police for two years claiming a mystery phone caller had been threatening to kill his family. The mystery caller was Birch’s first scapegoat for murder, but unable to explain his own blood all over his semi-detached home he changed his story and invented a bizarre tale of Samurai suicide. He admitted he faked the threatening phone calls and substituted a tale of ritual suicide, using a silk scarf as a talisman and a knife to plunge into his stomach. He said it was his way out of debt and worry. He claimed his plan was thwarted when his wife disturbed him in the act and in the ensuing struggle to gain control of the knife she was killed accidentally.

However, Birch’s behaviour afterwards sealed his fate. Prosecuting counsel Stuart Shields QC asked repeatedly why he hadn’t executed himself after his wife’s death? Why didn’t he go for help if it was an accident? Why had he coolly put blood splattered clothing and the knife into the Fiat to dump them in a lonely lane? And why had he carried on a bizarre charade, continuing to visit clients in Malvern and Kidderminster for two-and-a-half hours that day?

Birch could only say he panicked and wanted to run away because no-one would believe he had killed Gillian by mistake. After a five day trial the jury certainly didn’t believe him and two years later the Court of Appeal didn’t either, ruling its guilty verdict perfectly proper.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here