AS Christmas 1214 approached Worcestershire’s high society was all a-twitter. King John was on his way and intending to spend the festive season in the city.

In the event pressing business in London restricted his stay to just two days, but that was long enough for John to enjoy a Christmas feast of industrial, or right royal, proportions. An expenses audit of his trip carried out in London in January, showed that in Worcester John’s Christmas dinner had consumed no less than 50 deer and 60 pigs.

There were no turkeys because they didn’t arrive in England until around 1540.

No idea who signed the chitty, but apparently no eyebrows were raised.

In fact during the Middle Ages it was incumbent upon kings to dispense hospitality throughout the twelve days of the festival, and in Henry VIII’s reign more than a thousand people dined at court during the Yuletide season, with an Italian visitor noting that on one occasion the guests remained at table for over seven hours.

Henry VIII liked to keep Christmas at Greenwich Palace, his birthplace. Hampton Court was also favoured by the Tudor monarchs and the palace would be specially decorated for the Christmas period.

Despite the duration of the meal the table manners of the King and his courtiers were usually refined and decorous – apart from the time when Henry got bored and began pelting his guests with sugar plums.

In Worcester three centuries earlier John also took a day off, for Christmas Day produced no work recorded on the chancery rolls.

Back then presents were exchanged, not on Christmas Day, but on New Year’s Day when every courtier and servant gave the monarch a present, and – if they were privileged – received a gift in return.

For the sumptuous banquet that marked Twelfth Night, a special cake was baked. The cake contained a pea or a bean; whoever found it would be king or queen for the evening and lead the singing, dancing or disports..

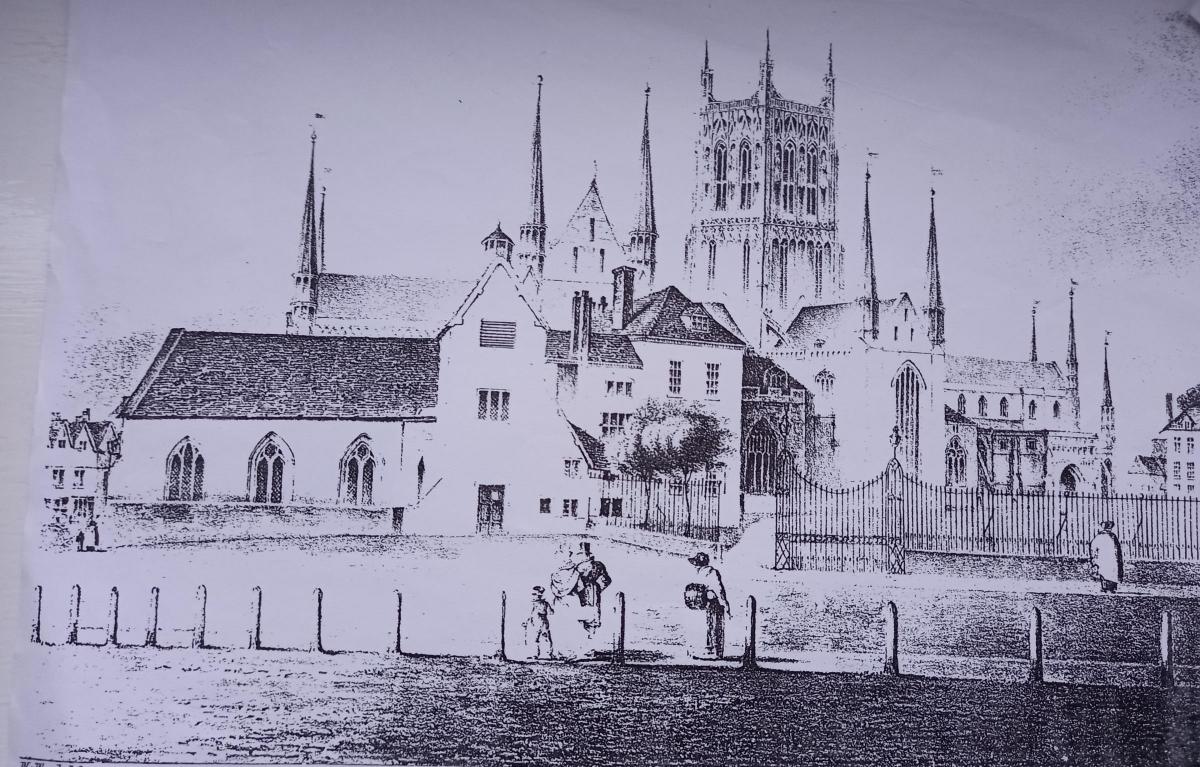

In Worcester the best New Year’s Eve party in town took place in the Cathedral Priory. The last of the priors, William More, reigned over a religious community whose strict rules of life had relaxed to the extent the jovial monks had come to understand very well the good things in life. They kept a small army of cooks and kitchen menials and no expense was spared when it came to filling their tables with the richest food.

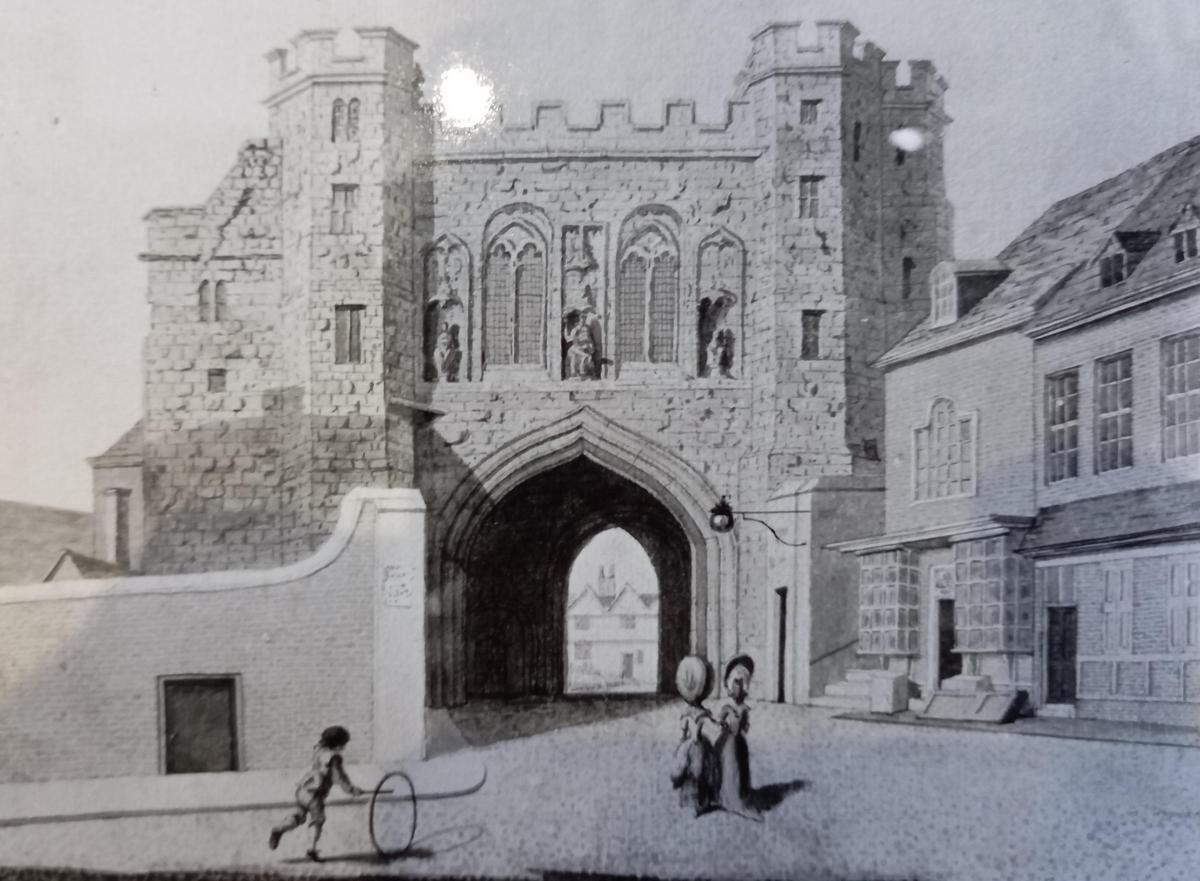

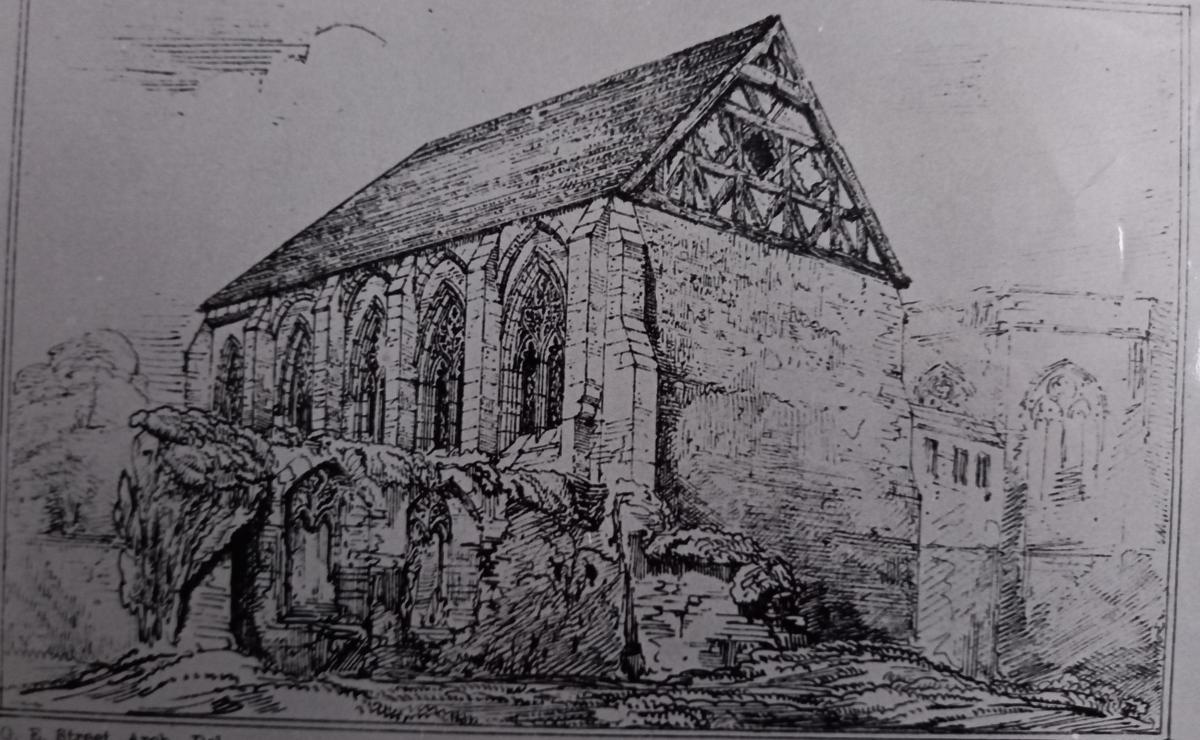

The roistering began after evensong on Christmas night when the prior and his brethren welcomed the city bailiff and his corporation (dressed in scarlet gowns) to a grand feast in the priory’s Guesten Hall, which had been built in 1320 for the monks to entertain visitors and guests.

The tables groaned under the weight of boar’s heads, numerous dishes of venison, game, dumplings, peacock pie and the like. Also served were oranges, then a costly imported delicacy. The food was accompanied by eight or nine varieties of sticky ales or wines, some so thick the guests filtered them through their teeth.

Meanwhile, about a hundred yards away, King John lay resting in his tomb in Worcester Cathedral probably wishing he could join in.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here