(standfirst)

THE latest article by Faith Renger on Malvern in the Great War takes a look at the problems posed by refugees and enemy aliens.

THE people of Malvern were keen to offer homes and support to some of the thousands of Belgian refugees who fled the German invasion of their country in August and September 1914.

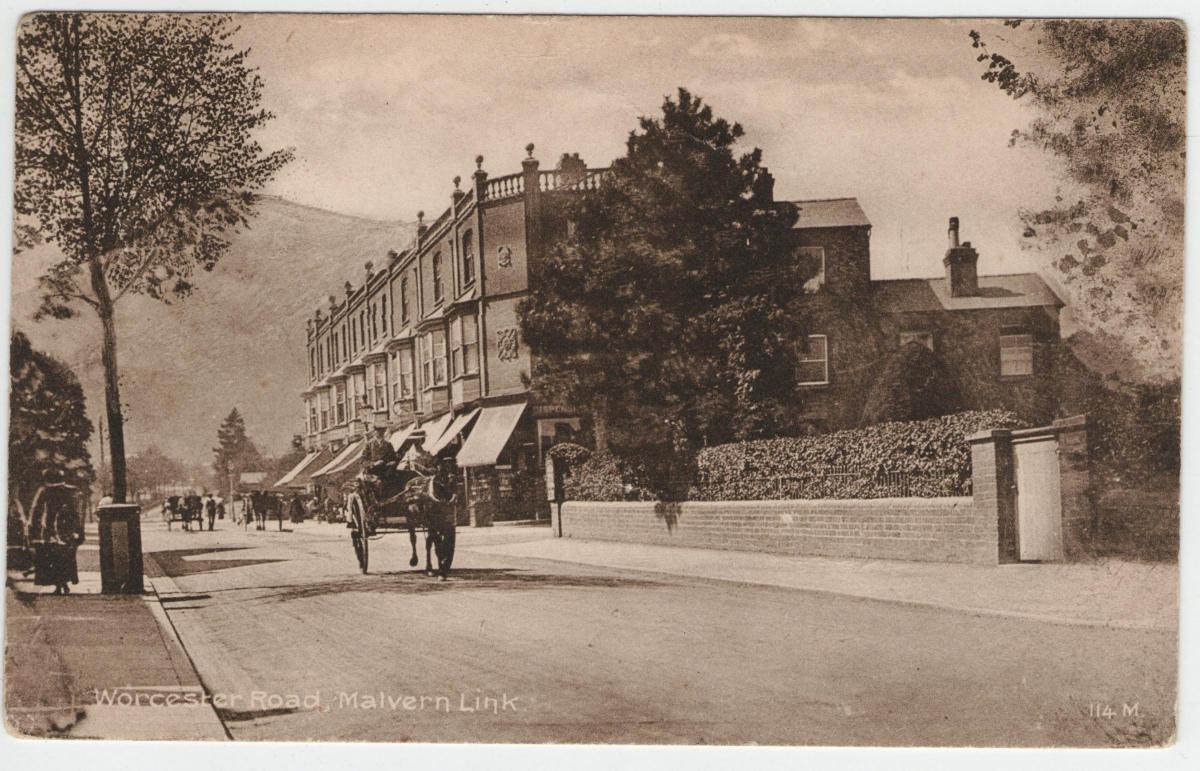

Thirty nuns from a convent near Antwerp were the first to arrive in Malvern in September. By then a hostel was being prepared for refugee families in the Colston Buildings terrace, Malvern Link.

Malvern Urban District Council had asked the War Refugee Council specifically for Belgian trades people since they could perhaps take over businesses which Malvern men had left to join the colours.

Some Belgian grocers were employed locally and watchmakers and coffee house keepers also found work. Belgian women made lace items, knitted clothes and supported local voluntary groups.

Malvern inhabitants gave generously to the Belgian Relief Fund and shops like Kendall's gave a percentage of their week's takings. The council agreed not to charge rents on the five hostels and also provided coal, electricity and water free of charge.

Kinnersley House in Malvern Wells took Belgian families throughout the war; two refugees were married at nearby St Wulstan's church and some children were baptised there.

In 1918 a large group of Belgian schoolchildren was transferred to Kinnersley and other empty houses in Malvern Wells to continue their education.

The story of one little Belgian child has featured on the BBC World War One at Home. Irene Stewart was just a few weeks old when she and her mother escaped on a coal boat.

They stayed in the Colston Building hostel initially. Irene's father was probably a Belgian Congo soldier though nothing is known about him.

Irene attracted a lot of interest because of her mixed race appearance and when her mother disappeared to look for work and failed to return, Irene was fostered by a family in Merton Road. Here she grew up and attended Somers Park school.

Other Belgians decided to return to unoccupied Belgium or France, some joining the remnant of the Belgian army. Altogether, Malvern provided accommodation, support and work for over 500 refugees.

Within days of war being declared the government passed the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA). It set down laws designed to safeguard threats to national security, such as lighting bonfires or talking to servicemen in public places.

An early DORA regulation aimed to control those living in Britain who had a German or Austrian background.

These people were referred to as aliens and they were expected to report to their local police station regularly.

Several reports in the Malvern Gazettes drew attention to local inhabitants who had lived in Malvern for most of their lives but had German surnames.

They were accused of harbouring rifles, acting as spies or plotting to burn down hay ricks. Six were arrested in November 1914 and sent to an internment camp in Newbury. Some, like Karl Wilhelm Elderachek, were sentenced to a term of hard labour.

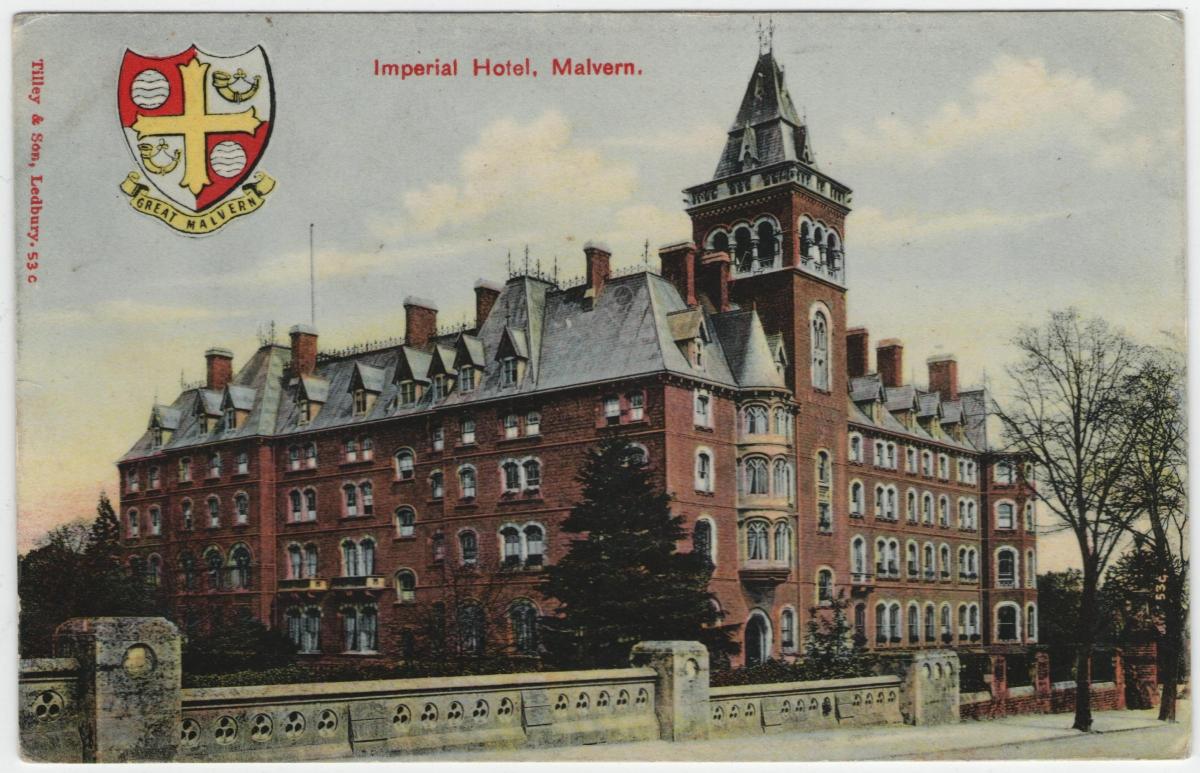

The owner of the Imperial Hotel, now Malvern St James, was a much respected elderly German businessman who also held office on the local town council.

Within days of war breaking out, Frederick Moerschell was subjected to much abuse and even an attempted assault. He had employed a number of Germans as waiters, all of whom had left Malvern at the beginning of August after receiving their call up papers from Germany.

Moerschell felt obliged to change his name to Marshall before DORA prohibited this.

Rumours of spies spread quickly, such as the German who was apparently caught at Malvern Link station carrying enough poison to contaminate the entire water supply for the town.

A German governess who had worked for a Malvern Wells family for many years prior to the war, was accused of owning a large number of maps that could be used by other spies.

An Austrian businessman who had retired to Malvern before the war, faced the prospect in 1918 of being forcibly repatriated to Austria, a country he hardly knew.

Frederick Brandauer was a millionaire whose fortune had come from the family firm that manufactured steel pen nibs in Birmingham.

He was arrested in Malvern in 1917 and interned on the Isle of Man. He chose to take his own life rather than return to his homeland.

These and other stories have come mainly from the Malvern Gazettes published during the war. Malvern Museum has produced three books covering life during the war as experienced by people in Malvern.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here